Exploring the full range of harmonics, using a variety of mallets and strikers - multi-instrumentalist Pete Moser is at it again.

A piece composed by Peter Conner and Andy Aitchison using the haunting sound of Marcus Vergette's Time and Tide Bell installation on Mablethorpe beach.

This is a different way of ringing a Time and Tide Bell... Multi-instumentalist and composer Pete Moser uses a soft and hard mallet. There are plans to repeat this every month....

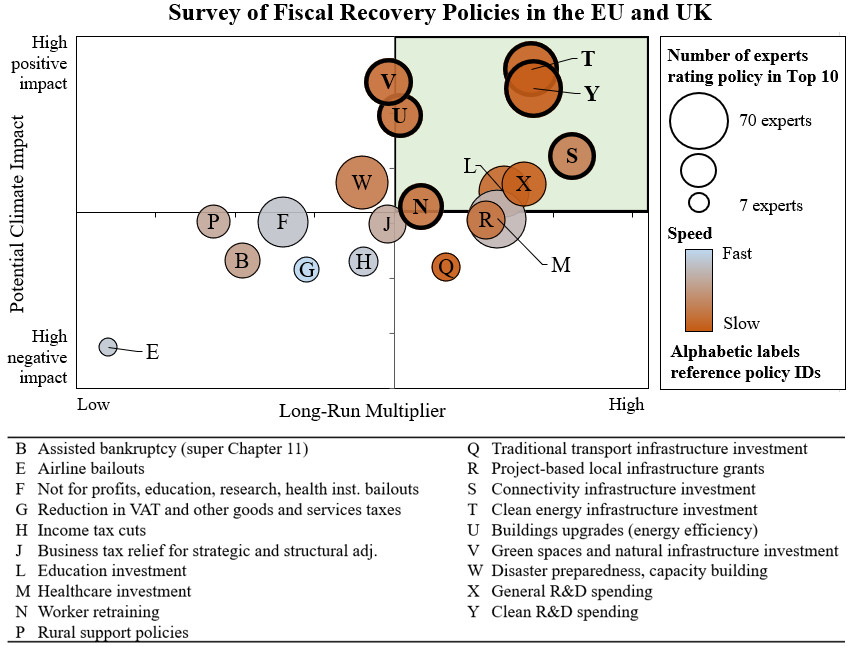

There is much current discussion of the form Government investment policy should take post-Covid-19. A study just published by the University of Oxford's Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, and covered in Carbon Brief looks at whether various possible fiscal recovery packages would accelerate or retard progress on climate change.

Short version, five policy recommendations stand out:

- Clean physical infrastructure investment in the form of renewable energy assets, storage (including hydrogen), grid modernisation and carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology;

- Building efficiency spending for renovations and retrofits including improved insulation, heating and domestic energy storage systems;

- Investment in education and training to address immediate unemployment from Covid-19 and structural shifts from decarbonisation;

- Natural capital investment for ecosystem resilience and regeneration including restoration of carbon-rich habitats and climate-friendly agriculture; and

- Clean R&D spending.

There is also this really interesting analysis of varied impacts on both climate change and financial benefits. Look at the benefit of bailing out the airline sector in the bottom left - low benefit, lousy climate consequences of course, but quick returns.....

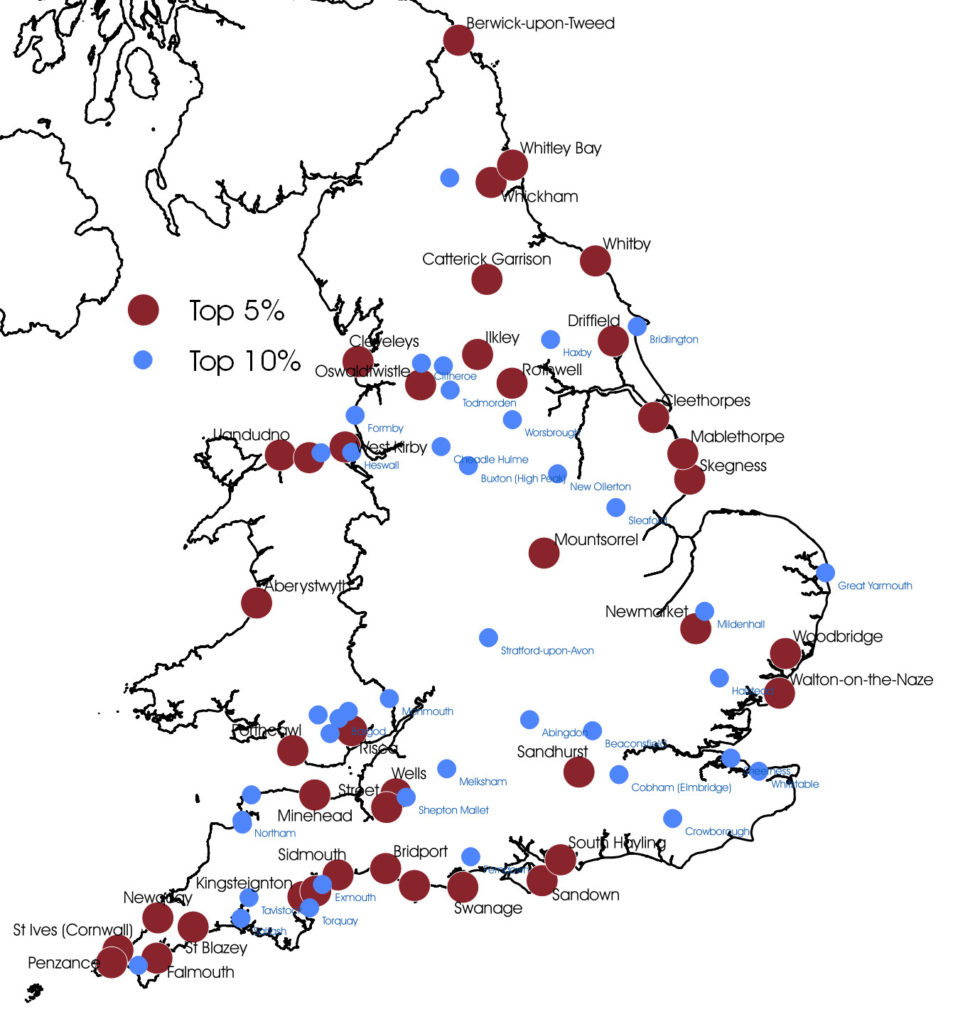

The thinktank The Centre for Towns has recently published a report called The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on our towns and cities. The Centre is 'an independent non-partisan organisation dedicated to providing research and analysis of our towns. Whilst our cities receive a good deal of attention, we believe that there should be equal attention paid to the viability and prosperity of our towns'.

The report makes sobering reading. Not only are seaside towns hit hard by the epidemic, but their ability to recover following the lockdown will be limited.

Over a half of employees in some places are currently in sectors which are effectively shut down. These places include Newquay in Cornwall (56%) and Skegness (55%) on the East Midlands coast. Coastal towns are disproportionately affected by the shutdown.

On average over a quarter of all employed people in coastal towns across England and Wales are currently employed in shut down sectors.

The closure of hotels, bed and breakfasts, campsites and caravan parks due to COVID-19 impacts upon coastal towns, with towns like Newquay, St Ives, Skegness, Llandudno and Rhyl particularly affected.

This map shows in red those towns that are in the top 5% of those in the country for the proportion of the working population employed in providing accommodation - and the large majority is on the coast.

What is our contribution to the challenge this poses? Good question - currently it's work in progress.

A virtual meeting was held on march 23, between the MBA team, Time and Tide Bell team, and some of those who had attended the workshops.

The first point was obvious - the radical changes to life in the UK due to the coronavirus epidemic have had a big impact on the project, taking place as they have at its most critical phase: trying to define its shape. There is a chance of extending funding until November.

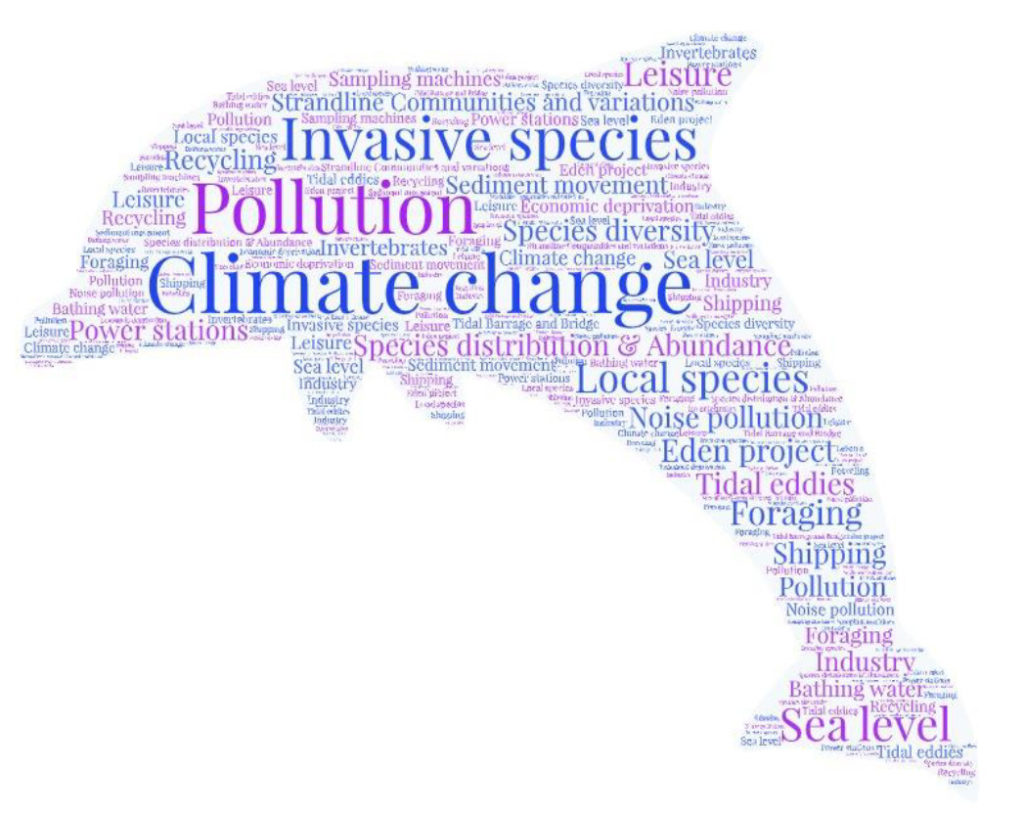

Jack Sewell ran through his draft report - which revealed much commonality between the different locations. This is well illustrated by a word cloud of the proposals put forward:

Similar work had been done on the must-haves for such a project:

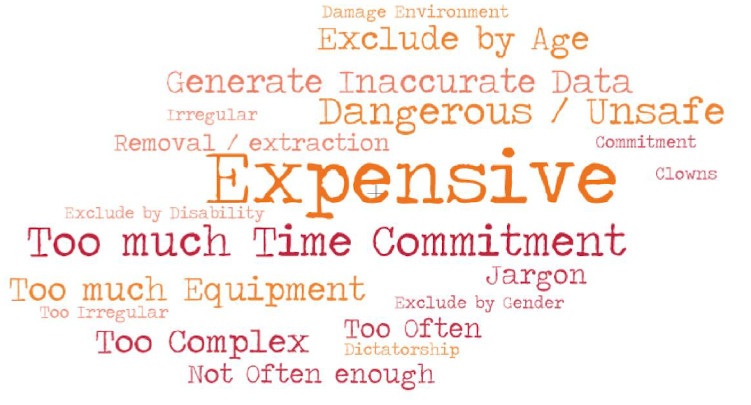

And the must-not-haves:

The project remains work in progress. Watch this space; all those who attended will be kept fully in touch with developments.

Most people reading this will probably know that there is a substantial, growing and deeply committed group of artists whose work aims to have a focus in some form on climate change. Whether it can be read as a cry of pain (e.g. the observation that ‘scientists can shout, artists can scream’) or as a more measured, nuanced or intellectualised response, there is a vast range of work that has a bearing on the subject.

In 2005 I started out in this field, forming an organisation eventually called TippingPoint, inspired in part by Bill McKibben’s observation: But oddly, though we know about it, we don’t know about it. It hasn’t registered in our gut; it isn’t part of our culture. Where are the books? The poems? The plays? The goddamn operas?

TippingPoint worked primarily in the UK, but also across the world, holding events that brought over 2,000 artists into close contact with climate researchers of one type or another, all with a view to stimulating conversations, collaborations – whatever would help inspire new work. We had no prescriptions or expectations of the people who attended, we simply wanted to create an environment in which new ideas might develop. We also commissioned over 25 new pieces of work, mostly theatre pieces.

My original hope for TippingPoint was that we would act as midwife, or marriage broker, to something that might emerge as a twenty-first century version of Silent Spring. After a while I concluded that given the cacophonous media times in which we live it was unrealistic to expect a single piece of work to have comparable impact. So I settled on a lesser ambition, of helping to bring about as much work as possible that would contribute to a rising tide of insights, revelations – and screams – that would help wake us up to the subject.

And I think that has happened. Recognition of the severity of the issue is currently at an all-time high (let us hope, devoutly, that it is sustained); this is due to many factors, including the weather, Greta Thunberg, David Attenborough, and much more. But I cherish the notion that what is often called ‘the cultural response to climate change’ has played its part, and this will continue. The countless artworks that have emerged don't, of course, tell the story simply, still less do they interpret or help communicate the work of scientists, as many of them wished; but they have created that rising tide.

I claim no part in the conception of the Time and Tide Bells, which is wholly due to Marcus Vergette. But he came to several of TippingPoint’s events, and it became clear to me that these are not only very powerful sculptures, but that the ethos that surrounds them, the fact that they are a gift, without strings, to the communities that host them, and that they have the capacity to stimulate further work of a broad range, tells exactly the right story for our times.

And I think that if you listen to them really, really carefully, you can hear the sound of the sea level rising.

Peter Gingold

February 2020